Making Aliases

In some situations, we need to follow multiple naming conventions at the same time. For instance, it's a common approach to convert fields of some structure from camelCase (or another case) to snake_case to follow Python’s naming conventions.

Tip

If you don't know what are "snake_case", "camelCase", "Header-Case" and why you need to convert cases, visit Motivation/Converting Case

When you call routed function(method), Sensei collects argument names and adds the corresponding key to request arguments.

Assume, we have to make the following request:

POST /users HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

{

"firstName": "John Doe",

"birthCity": "Manchester",

...

}

Since the argument's name corresponds to the key in routed function's request arguments, you need to write this code:

@router.post('/users')

def create_user(firstName: str, birthCity: str) -> User:

pass

But this code violates Python naming conventions. For instance, PyCharm warns you that "Argument name should be lowercase." Because, according to the conventions, arguments in Python should be of the snake_case. To resolve this issue, you can use Case Converters.

Case Converters¶

Case Converter is a function that takes the string of one case and converts it to the string of another case and similar structure.

Example

This function converts a string to snake_case

def snake_case(s: str) -> str:

s = re.sub('(.)([A-Z][a-z]+)', r'\1_\2', s)

s = re.sub('([a-z0-9])([A-Z])', r'\1_\2', s)

s = re.sub(r'\W+', '_', s).lower()

s = re.sub(r'_+', '_', s)

return s

Sensei has a few built-in case converters:

- snake_case

- camel_case

- pascal_case

- constant_case

- kebab_case

- header_case

They are all closed relative to each other. This means if

we take any provided case converter, we can use it with any other supported case (case related to one of the built-in

case converter).

For instance, snake_case("myString") == my_string, snake_case("MY_STRING") == my_string, etc...

Math Definition

There is an explanation for the closure property of case converters for math lovers.

Definition Let C = {f1, f2, ..., fn}, is the set of functions, fi : Di -> Ei.

{f1, f2, ..., fn} closed relative to each other <=> ∀ k, m ∈ {1, ..., n} and ∀ x ∈ Dk

condition fk(x) ∈ Dm is met

Corollary Dk = Ek = Dm = Em = D ∀ k, m ∈ {1, ..., n} => {f1, f2, ..., fn} closed relative to each other.

Let's introduce an auxiliary function - rcase(str) = random_caseC(str).

This is the function, that chooses a random case from C and converts string str to the chosen case.

Here is an illustration of this closure property.

graph LR

A[str] -->|passed to function| B{"rcase(str)"};

B --> |converts to| C[result];

C --> |can be used as arg again| A;

A ---->D[final result];Case Converters can be used for converting case of request parameters and keys of JSON response.

But it's important to know, that case converters in the following three examples work only at the first nesting level without touching nested models. Let's explore how to apply converters.

Router (Router Level)¶

You can pass case converters as arguments to the Router constructor. This process is called "applying case converters at

Router level."

<param_type> corresponds to the <param_type>_case argument in the Router constructor, where <param_type> is

path, query, etc. And there is response_case that corresponds to the conversion of response fields.

Let's assume we have the API using camelCase:

from sensei import Router, camel_case, snake_case

router = Router(

'https://api.example.com',

body_case=camel_case,

response_case=snake_case

)

@router.post('/users')

def create_user(first_name: str, birth_city: str, ...) -> User:

pass

The example above converts parameters like first_name to firstName, birth_city to birthCity, etc.

When parsing JSON response, the example performs the reverse process, that is converts

firstName to first_name, birthCity to birth_city, etc. Here the original response case is camelCase because we

assume that API is good-designed and keeps input and output cases the same.

Info

Default value of header_case is header_case converter

from sensei.cases import header_case as to_header_case

class Router(IRouter):

def __init__(

...

header_case: CaseConverter | None = to_header_case,

):

Because headers are called this way:

- X-Token

- Content-Type

- etc...

Route Decorator (Route Level)¶

You can pass case converters as arguments to route decorator. This process is called "applying case converters at Route level." These converters have higher priority, than router level converters.

Arguments, responsible for applying converters, have the same names as the Router constructor.

Tip

If API is bad-designed and follows different name conventions at the same time, you can use it. For instance, all endpoints accept request body with keys of kebab-case, but one "rogue" endpoint accepts keys with keys of camelCase.

from sensei import Router, kebab_case, camel_case

router = Router(

'https://api.example.com',

body_case=kebab_case

)

@router.post('/users', body_case=camel_case)

def create_user(first_name: str, birth_city: str, ...) -> User:

pass

Class Hooks (Routed Model level)¶

When you use Routed Models, you can define converters through hooks.

<param_type> corresponds to __<param_type>_case__ hook. This process is called "applying case converters at

Routed Model level." Let's look at the example below:

router = Router(host, response_case=camel_case)

class User(APIModel):

@classmethod

def __header_case__(cls, s: str) -> str:

return kebab_case(s)

@staticmethod

def __response_case__(s: str) -> str:

return snake_case(s)

@classmethod

@router.get('/users/{id_}')

def get(cls, id_: Annotated[int, Path(alias='id')]) -> Self: pass

Hook function can be represented both as a class method and as a static method, but not instance methods.

So, response_case=camel_case in Router

router = Router(host, response_case=camel_case)

Will be overridden by hook __response_case__

@staticmethod

def __response_case__(s: str) -> str:

return snake_case(s)

Consequently, this level has the same priority as router level, because it replaces it. As well as router level level, it has lower priority than route level.

Hook Levels (Priority)¶

Code that handles intercepted function calls, events, or messages passed between software components is called a hook. The levels that were described above determine the scope of applying some hooks. In the context of this article, hooks are the case converters.

- Router Level: apply hook to each routed function associated with that router

- Route Level: apply hook only to this routed function

- Routed Model Level: apply hook to each routed method associated with that model. Replaces Router Level.

Moreover, there are different types of hook levels, each of which has a special property. In the case of case converters, this type is called Priority Levels. Because, if multiple hooks are applied to one target (routed function), only one will be executed, based on its priority. They can be described in that diagram:

flowchart

RoutedModel["Routed Model Level (Second Priority)"] --> |replaces| Router["Router Level (Second Priority)"]

Route["Route Level (First Priority)"] ---->|priority over| Router["Router Level (Second Priority)"]

style Route fill:#C94A2D,stroke:#000,stroke-width:2px;

style RoutedModel fill:#D88C00,stroke:#000,stroke-width:2px;

style Router fill:#2F8B5D,stroke:#000,stroke-width:2px;AliasGenerator¶

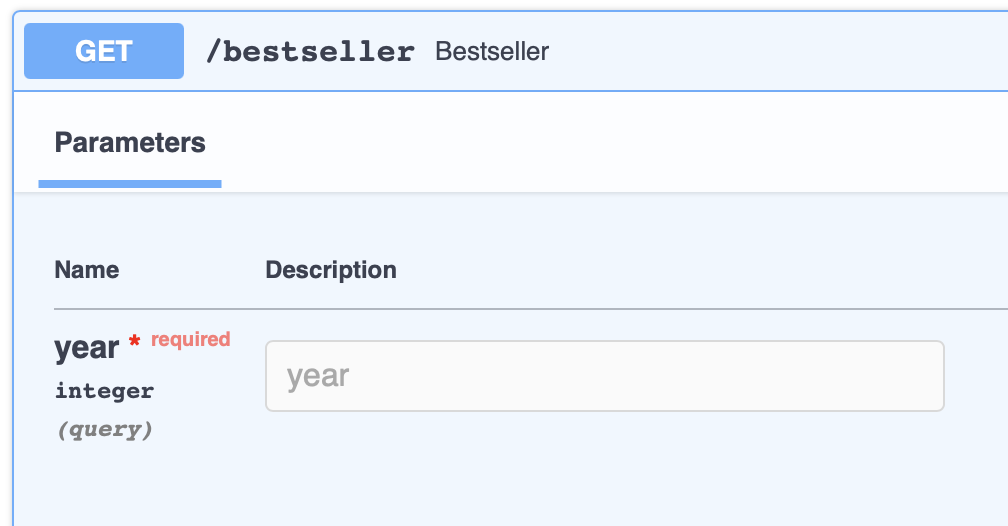

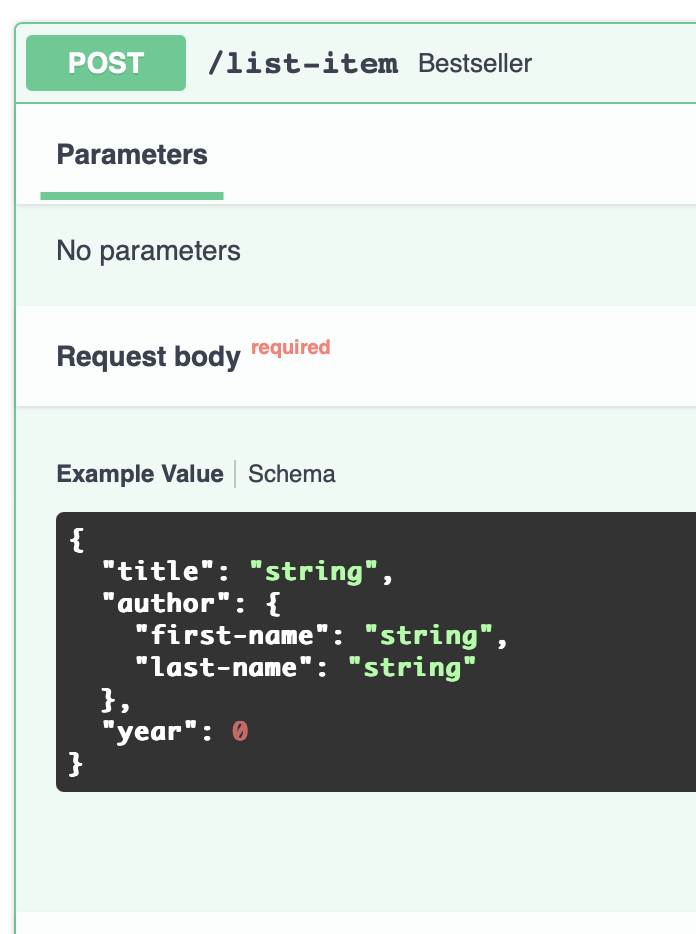

What if we need to apply case converters at the deeper nesting levels? Assume the API has two endpoints:

1) For getting a bestseller of a specific year

2) And publishing book for a sale.

For some reason, the first endpoint returns a response of camelCase, but the second endpoint accepts a book of kebab case. To follow Python naming conventions, you have to make snake_case attributes. At the same time, you need to make only one model that can handle both the kebab-case and the camel_case, to follow DRY.

Info

Even if the case of the first and second endpoints are equal, you still would not be able to apply anything other than

the approach described below, because the Book has a nested Author model. Cases are not equal only to show what are

validation_alias and serialization_alias in one example.

You can't apply case converters through router, route decorator or class hooks, because they can be used only

at the first nesting level. To achieve the goal, you can use the AliasGenerator class from pydantic with the

model_config attribute.

from sensei import APIModel, camel_case, kebab_case, Router, Body

from pydantic import ConfigDict, AliasGenerator

from typing import Annotated

router = Router('https://api.example.com')

SHARED_CONFIG = ConfigDict(

alias_generator=AliasGenerator(

validation_alias=lambda field_name: camel_case(field_name),

serialization_alias=lambda field_name: kebab_case(field_name),

),

populate_by_name=True # (1)!

)

class Author(APIModel):

model_config = SHARED_CONFIG

first_name: str

last_name: str

class Book(APIModel):

model_config = SHARED_CONFIG

title: str

author: Author

year: int

@router.get('/bestseller')

def get_bestseller(year: int) -> Book:

pass

@router.post('/list-item')

def list_item(book: Annotated[Book, Body(embed=False)]) -> None:

pass

- Allows using both original field names and aliases

Let's explore what's going on.

Validation Alias¶

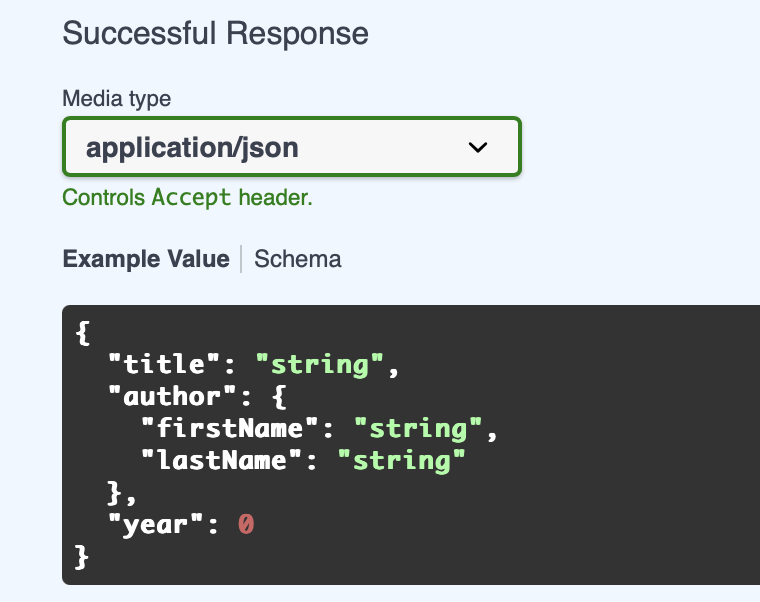

The validation alias is used when validating incoming data in models. That appears when Sensei unpacks the response to some model.

In this example, the validation_alias lambda function takes a field name and converts it to camelCase.

When you access the /bestseller endpoint, Sensei handles the response of camelCase by unpacking it to the Book model.

At the same time, Book accepts fields of configured validation_alias, that is camelCase.

@router.get('/bestseller')

def get_bestseller(year: int) -> Book:

pass

Let's break this routed function down into steps:

1) Making HTTP request and getting a similar response:

{

"title": "1984",

"author": {

"firstName": "George",

"lastName": "Orwell"

},

"year": 1949

}

book = Book(

title="1984",

author={'firstName': 'George', 'lastName': 'Orwell'},

year=1949

)

Author model uses AliasGenerator to convert original field names to the chosen case and compares with input

in the model constructor. firstName corresponds to first_name, lastName to last_name etc.

3) Returning the result

Serialization Alias¶

The serialization alias is used when serializing the model using model_dump(by_alias=True).

That appears when Sensei serializes request arguments represented as some model.

In this example, the serialization_alias lambda function converts field names to a camelCase.

When you access the/list-item endpoint, Sensei handles the arguments of the routed function by serializing it by

model_dump(by_alias=True) and pass it into request parameters.

@router.post('/list-item')

def list_item(book: Annotated[Book, Body(embed=False)]) -> None:

pass

You can use original field names along with aliases, because SHARED_CONFIG includes populate_by_name=True.

list_item(Book(

title="1984",

author={'first_name': 'George', 'last_name': 'Orwell'},

year=1949

))

Tip

If validation_alias and serialization_alias are equal, you can use the alias argument.

SHARED_CONFIG = ConfigDict(

alias_generator=AliasGenerator(

alias=lambda field_name: camel_case(field_name),

),

populate_by_name=True

)

Field-Specific Aliases¶

In some cases, you may want to apply a specific alias for a certain field.

from pydantic import ConfigDict, AliasGenerator, Field

...

class Book(APIModel):

model_config = SHARED_CONFIG

title: str

author: Author

year: int = Field(

validation_alias="pubYear",

serialization_alias="publication-year"

)

This specific alias takes precedence over the AliasGenerator, which means that even though other fields

are transformed by the generator, year will be serialized as publication-year

and validated as pubYear

Info

The same approach can be used in params aliases:

@router.post('/list-item')

def list_item(book: Annotated[Book, Body(alias="bookForSale", embed=False)]) -> None:

pass

But validation_alias and serialization_alias can't be used like before. The argument alias means the same

as serialization_alias.

Recap¶

In Sensei, managing different naming conventions (like camelCase, snake_case, etc.) is crucial for building APIs that conform to Python's standards. Here’s a concise summary of the key concepts:

-

Case Converters: Built-in functions that convert strings between various cases. Examples include

snake_case,camel_case,header_case, etc. These converters are closed relative to one another, meaning you can interchangeably apply them. -

Router Configuration: The

Routerconstructor allows you to specify case converters for request bodies and responses. This ensures that parameter names in your function match the expected format of the API. -

Route Decorators: You can apply a converter taking precedence over the corresponding

Routercase converter, by providing it directly in the route decorator. This is useful for handling endpoints that do not conform to the general conventions. -

Class Hooks: For Routed Models, you can define case converters through

-

Class Hooks: For Routed Models, you can define case converters through class hooks within your model classes.

-

AliasGenerator: When dealing with nested models and varying case conventions (like camelCase for responses and kebab-case for requests), the

AliasGeneratorfrom Pydantic is utilized. It allows for defining separate validation and serialization aliases. -

Field-Specific Aliases: For certain fields requiring unique aliasing, you can specify individual aliases using the

Fieldclass. This takes precedence over the generic alias generation.

By leveraging these tools, developers can effectively manage API naming conventions and ensure seamless integration with Python’s style while adhering to DRY principles.